Seeing the Show

A photographic reproduction is obviously a way of getting to know a work. But the matter of documentation by way of photographing works on view in exhibitions calls for a broader line of thinking about photography as a tool in creative work, and one which goes beyond the challenges of conservation, distribution and media coverage.

The ever greater number of media for publishing and distributing photographic documentation of exhibitions, especially with the Internet, makes the media coverage of an event, as well as its storage and even its recording as heritage1, that much easier. And this certainly affects our perception of the work of art. We are witnessing a de-contextualization involving a re-interpretation which quite often risks altering the nature of the work and the author's idea.2

The Documents d'Artistes databases are distinctive for being compiled in collaboration with the artists in question. Photographs of works, and reproductions, go hand in hand with views of exhibitions, descriptive notes, essays, and video and sound excerpts. Documentary resources, for their part, are used in differing ways. The documents brought together and associated are just as much tools for artists, curators, critics and students as they are a source of information for different kinds of public.3

The Documents d'Artistes project is being constructed as a network.4 Each base has its own website, with a specific graphic identity which nevertheless borrows a shared structure. The entries—index of works, bio-bibliographies, texts and references are all to be found in the four bases; some incorporate a "current" entry (actualité) in the dossier, others on the website's homepage. The principle of a mosaic of images for opening the dossier regularly crops up, though not systematically, and these images will go to make the different headings which are organized in quite different ways from one artist to the next.

The index of works operates in a way like a visual memory system (an image is easier to memorize than a text), with an image sometimes re-framed in a square format, of varying types: reproduction, typography, drawing and exhibition view. So getting into the dossier is usually done through images, vignettes associated with the titles of the headings. So it is the text-image association which steers the directory structure, with certain dossiers requiring an intermediary index. This architecture reflects the plural nature of the praxes and activities, with their special features being included in a platform, a common interface.

The difficulty of the system in fact still resides in associating 400 artists without levelling off the different works through the dossier format. It is by way of the discussion with the artist at the moment of preparing the dossier that an identity tallying with the interface is conceived, despite the nomenclature and the desire to respect DDA's graphic principle. In this way, certain artists take into account the conditions of the digital environment and construct a specific form of display for their work, within the context of the dossier. Paradoxically, this particularly interesting approach seems to be the most coherent one in terms of integrity.

As a result, what are the artistic and scientific challenges of the documentary representation of an exhibition in the context of an online database?

1-The exhibition view, a relevant solution for describing the activities of today's artists.

There are many databases made up of images of artworks, but mainly around the collection idea (Joconde/Mona Lisa). The culture.fr portal in particular holds several such bases, like those of the Louvre Museum and the National Archives. They are the outcome of lots of collection digitization campaigns, as well as documentary collections. The INHA (National Institute of Art History) offers an illustrative guide encompassing 145 image databases in 16 countries, representing a corpus of 6 million images. Then there are purely illustrative bases like Mémoire, a catalogue of stills coming from the Architecture and Patrimony Media Centre as well as from the regional departments of the General Inventory, Historic Monuments and Archaeology. In terms of periods and intentions, the Vidéomuseum database is the closest to the DDA, forming a network of French museums and organizations managing modern and contemporary art collections (national, regional, departmental and municipal museums, FNACs and FRACs—National and Regional Contemporary Art Collections--, and foundations). It is based solely on collections and each establishment describes the works using a common thesaurus containing the following indexes: "Artist's name; Type of work; Domain, denomination; Materials, medium, technique".5

Documents d'Artistes and Vidéomuseum are run by associations. It might be useful to take a look at their histories, and the way these projects have been set up, to understand their original intentions and their goals today. During the 1990s, with the institutional beginnings of the Internet (Vidéomuseum still offers a CD-Rom), there was a desire to create a national database developed on XML, with a system of keywords. Several structures were then associated, bringing together around the table archivists and data processors to introduce a vocabulary in the spirit of the semantic Web. The original conception of these databases still directs their interfaces to this day, and thus also the nomenclature system forming the typology and terminology of the various media and disciplines, and consequently the way of browsing and perceiving the works. Searches are made using words, not images, and so the writing of the picture captions and in a more general way the indexing are especially decisive. The challenge these days is inter-operability, meaning the overlapping of these different bases and the introduction of a common search engine. Private programmes such as Kapsul.org are headed in this direction today.

What makes these bases most distinctive is their uses and their users. The specific feature of DDA is to be closer to artists, with the base being constructed in a dialogue with them. Vidéomuseum is an institutional base which makes it possible to manage collections, and loans of works in particular, so it is becoming a tool not only for museum curators but also for freelance exhibition curators who can make their "selection" of works and artists in it, based on documentary photos. For users, DDA differs from Vidéomuseum by addressing not only museum and exhibition curators, historians and researchers, but art lovers in general too. Even if this is a powerful documentary resource, it is neither exhaustive nor scientifically organized, because it is filled with images and data supplied by the authors themselves.

Vidéomuseum does not take the issue of the exhibited work into consideration. It is not possible to undertake searches by exhibition. Nor is DDA a base organized on the basis of the exhibition notion but, as a result of the dialogue between the DDA teams and artists, the interface is adapted to artistic praxes and current concerns with issues of display, hanging, layout and online publishing. This is an important factor for understanding the challenges of distributing documents about a work and more particularly about a work being exhibited, in a given venue at a given time. Some dossiers are made up exclusively of exhibition views, while for others there will just be reproductions of the works in question. These situations are meaningful because some artists work on the placement and showing of their works in relation to others. The documentation of the exhibition is thus preferred. The nature of the documents, the way they are presented, and the preparation of the interface are the consequences of an art praxis. "You don't isolate the piece when it makes no sense in the artist's work. We are attentive to the logic of the work; when it's a photographer, we're not necessarily going to highlight the exhibition views, unless this creates particular displays or to show the ratio of scale of the works."6 The difference between representation of works and exhibition views is made on a case by case basis.

Works exist more and more in exhibition situations and not in an autonomous way. DDA helps us discover the same work documented from different angles, in different contexts, in relation to other works. There are two main interfaces for presenting images in artist's dossiers: they are either vertically aligned, and one scrolls through them, or there is a slide show with, on the left of the caption, two 'previous/next' arrows, and you thus discover the views one by one. The interface does not make it possible to juxtapose them otherwise or overlap them to make a comparative analysis.

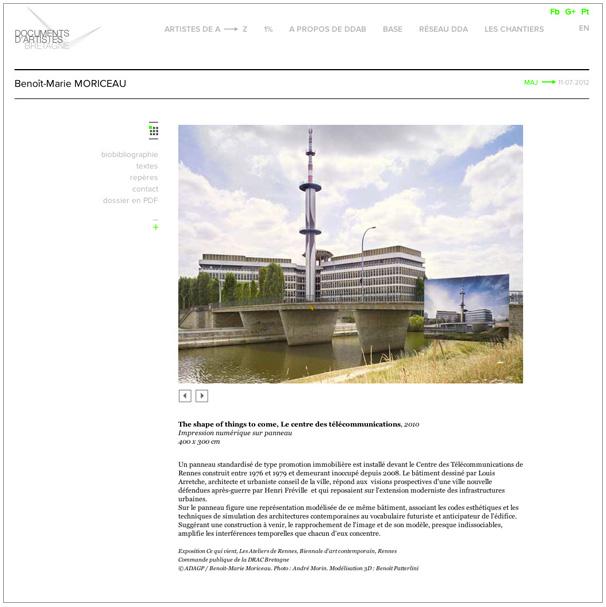

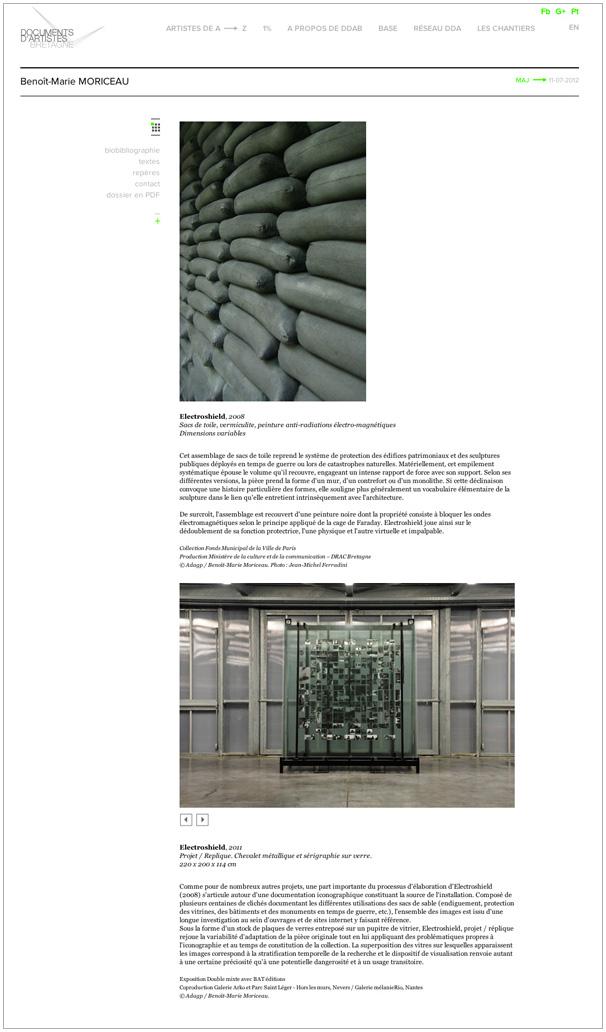

Benoît-Marie Moriceau's dossier is made up of several slide shows; the piece The Shape of Things to Come, Le Centre des Télécommunications, 2010, is a digital print on a large panel (400 x 300 cm) depicting a modelled representation of a building. The slide show consists of a view presenting it in an "exhibition situation", the image on the panel is juxtaposed with its model, then with a reproduction of the modelled image. The photographer André Morin, who regularly works with the artist, produced the view of the work in its context, with reference to the image used as a basis for the modelled representation. The framing, the viewpoint, and the focus are identical. Through an interplay of repeated duplication (mise en abyme), the challenges of the representation overlap with those of the presentation. The piece Electroshield, 2008, an installation made of canvas sacks, is represented by a detailed view which precedes an explanatory text. Then a slide show presents Electroshield, 2011, a work deriving from the previous one, using the illustrative documentation that is part and parcel of the process of developing the work, composed of several hundred photos recording the different uses of the sacks of sand, like protecting the monument. Archival images are associated with a view of the installation. The captions of the pictures provide information about the work and not about the title and the exhibition venue which are mentioned at the foot of the page. Priority is thus given to the work's description, and less to the consequences of the variations in perception imposed by the exhibition contexts.

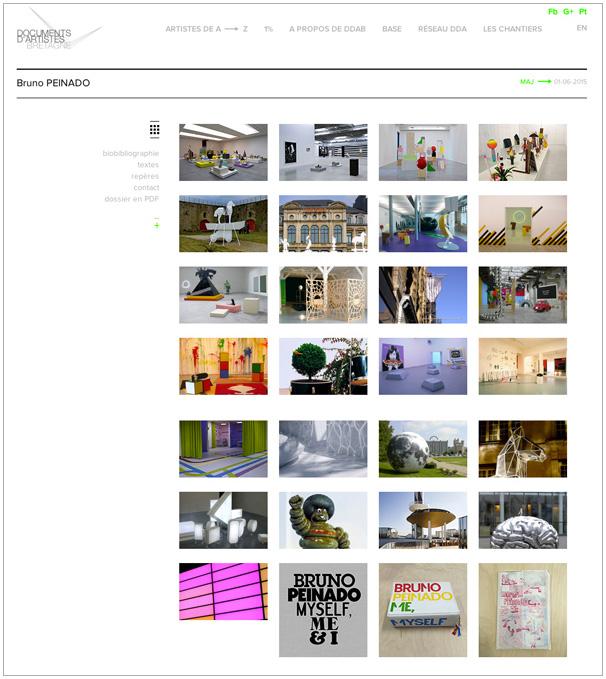

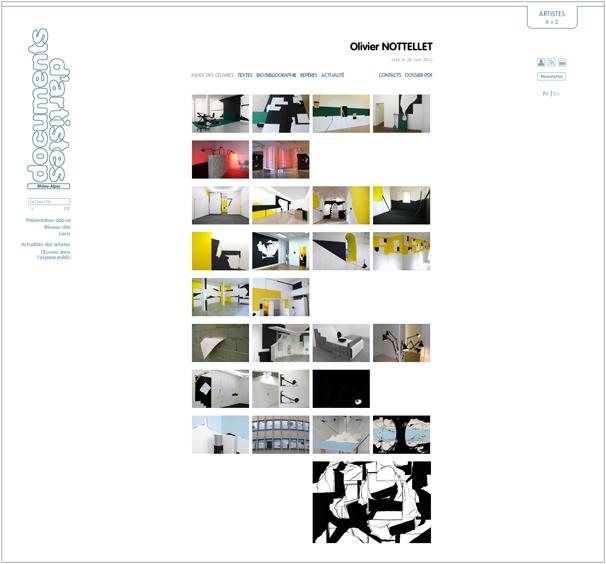

The headings in Bruno Peinado's dossier tally with the exhibitions. The approach to his works is thus essentially made when they are in an exhibition situation. We find certain pieces in different contexts which explains his praxis, and his involvement in the spatial arrangement of the work. In an even more obvious way, Olivier Nottelet works with the places in which he exhibits, and his dossier is organized by project and thus by exhibition, which echoes the approach.

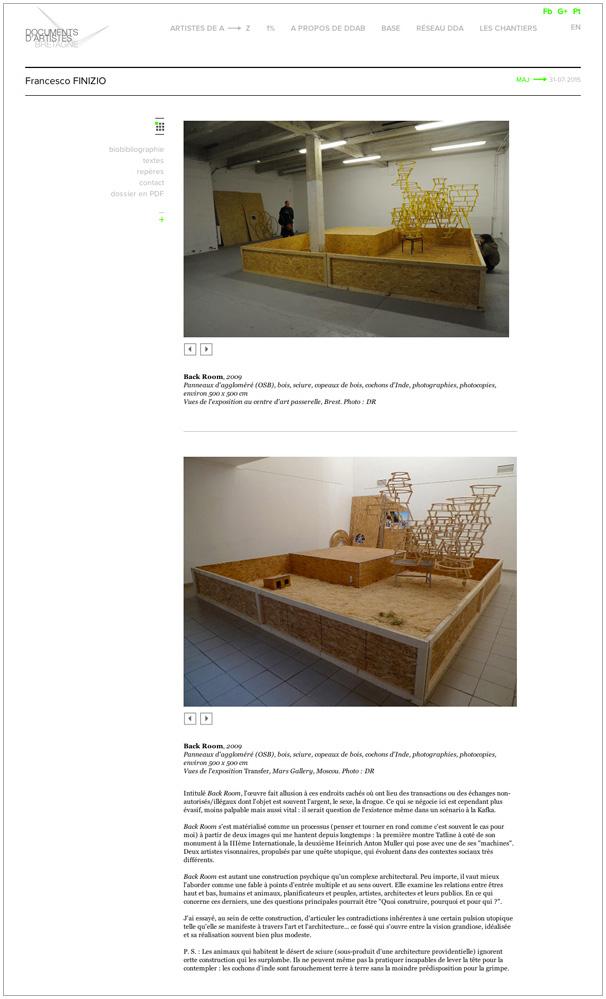

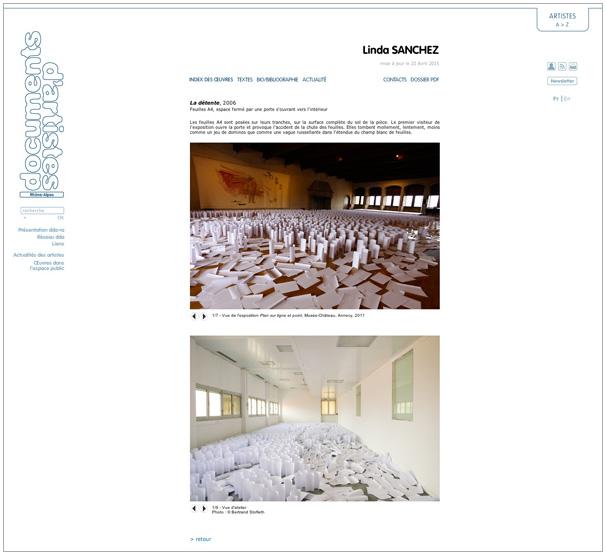

How I Went In & Out of Business for Seven Days and Seven Nights, 2008, by Francesco Finizio is a slide show of 97 pictures, made from a weeklong performance at the ACDC gallery in Bordeaux. It is presented in the dossier in video form, using the slide show which is part of the work. The exhibition ArtParkCraftRaftClinicClubPub, shown at the Museum of Bat Yam in Tel Aviv in 2015, included a large number of the artist's installations, and the views made in it illustrate several headings in the dossier, creating a link between the different projects. This also makes it possible to compare the installations in different contexts. Similarly, the views of the exhibition Plan sur ligne et point, of Linda Sanchez's work, at the Musée-Château d'Annecy in 2011, illustrate the headings of her different projects,. For the work La détente, an installation inextricably bound up with the volume of the place containing it and with the way visitors enter the space, two slide shows are in dialogue, one presenting the work in Annecy, the other in the studio.

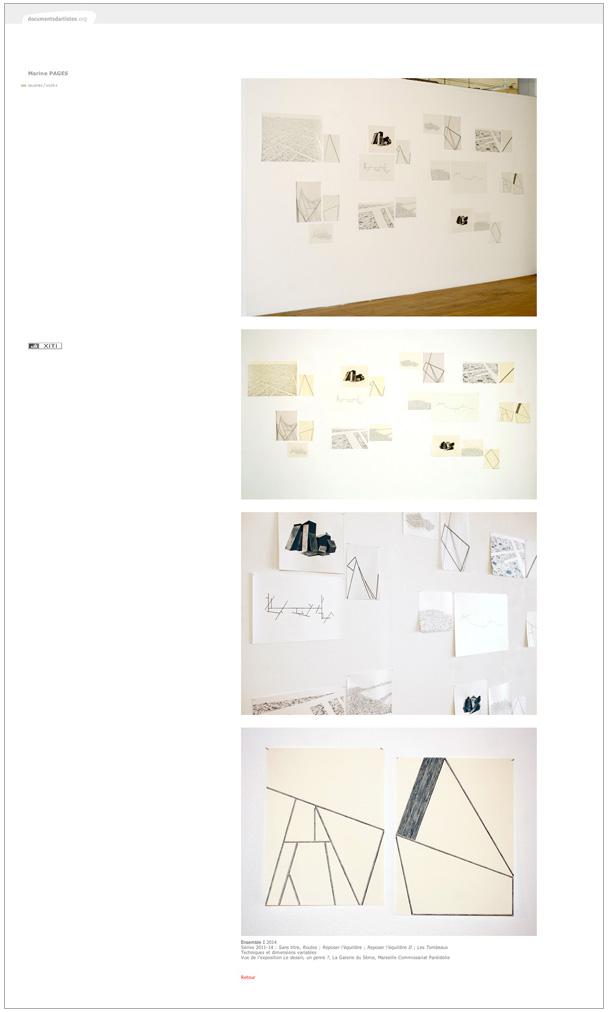

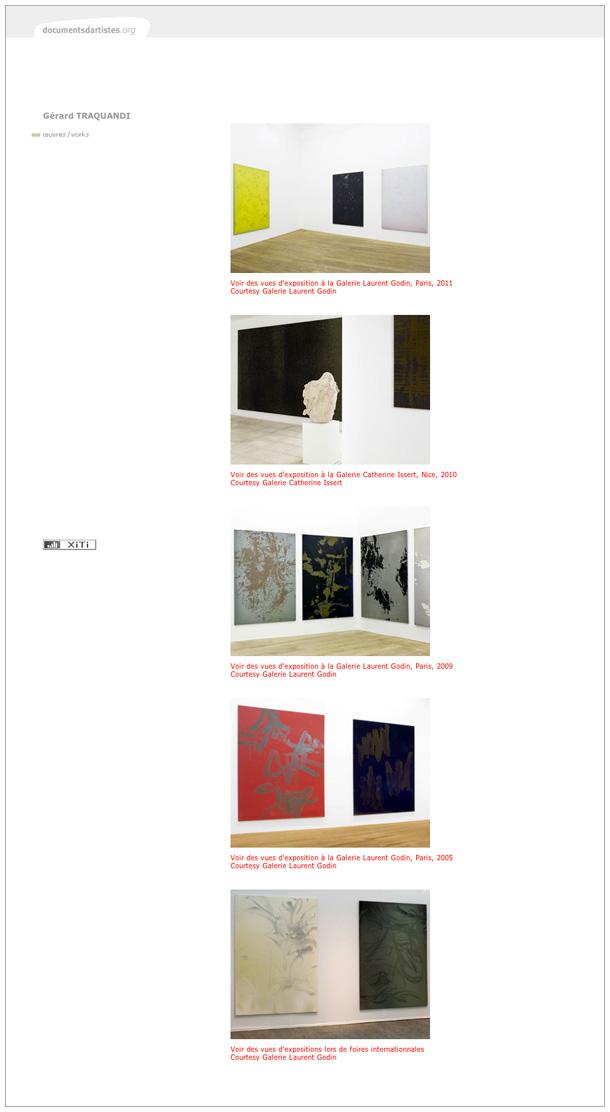

Marine Pagès's dossier presents reproductions of her drawings associated with exhibition views emphasizing the significance of the way they are hung and helping to show them in different configurations, either alone or in series. Reproducing painting, and monochromes in particular, in photographs has always posed a problem. Gérard Traquandi works on the matt quality of the medium: presenting his work on a screen, a source that is not only shiny but also luminous, and radiant, poses a problem. His dossier lets us see the works in reproduction as well as in exhibition situations, and studio views are required to describe his line of thinking and the process of the painting.

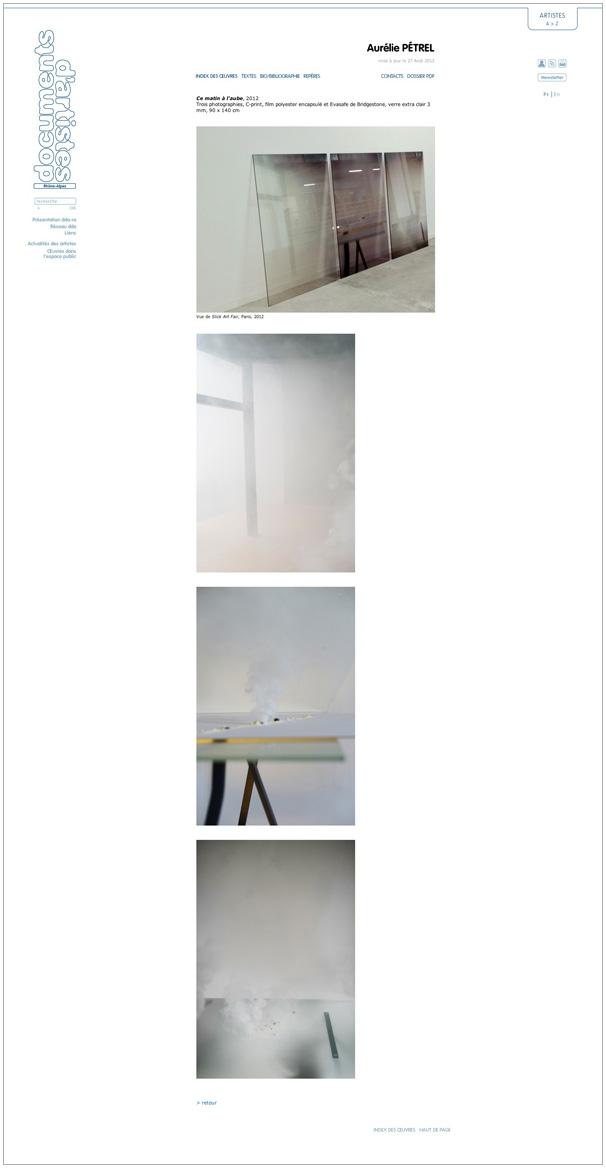

Aurélie Pétrel works on photography in its relation to space and develops the image's physicality—she incorporates the photograph in the place. The exhibition view is necessary to grasp this connection in relation to the source photograph, whose reproduction alone would not make it possible to understand the approach.

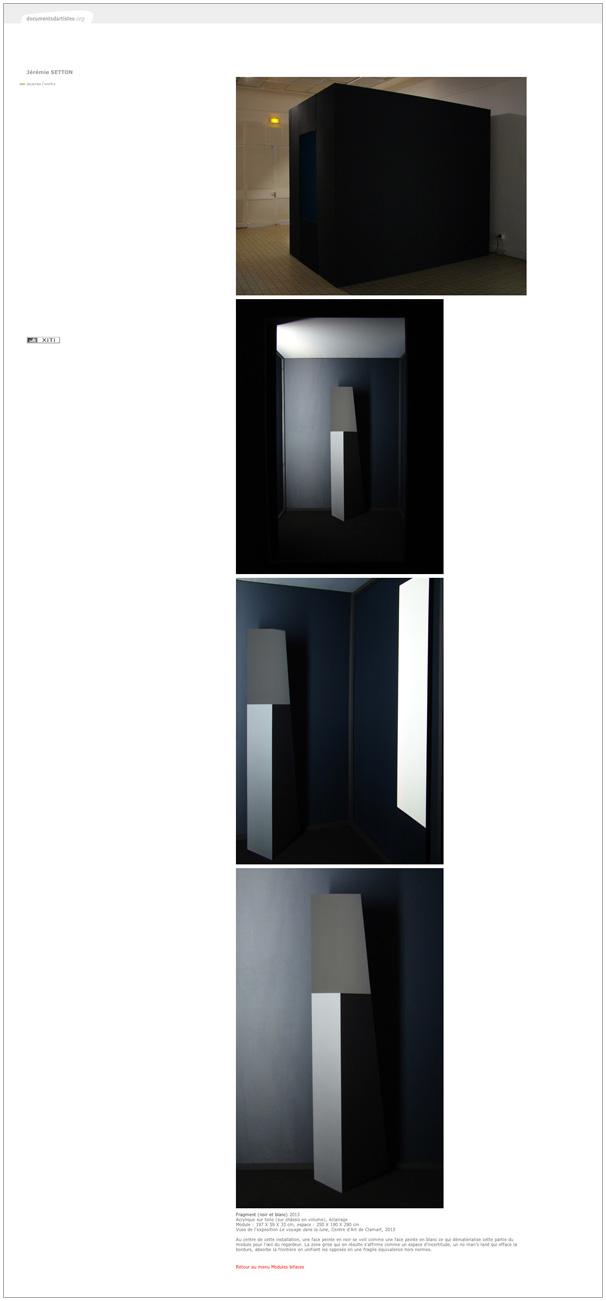

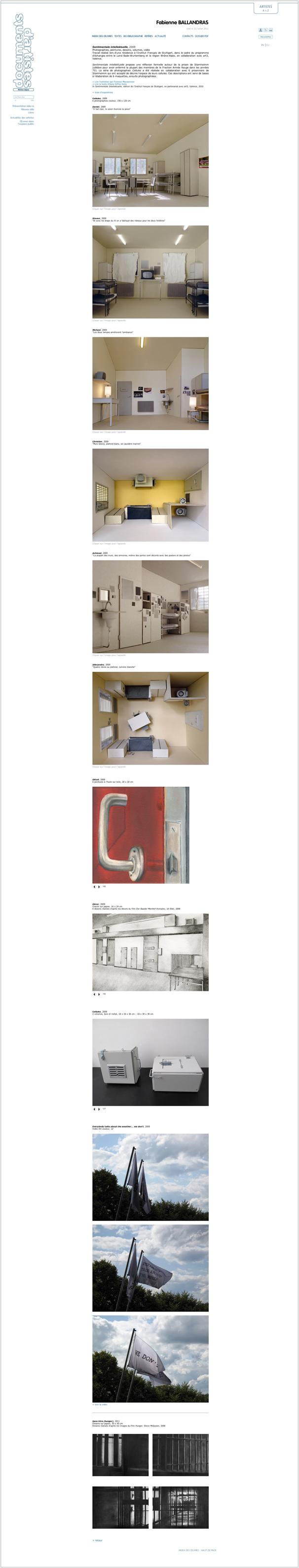

Jérémie Setton's exhibition views are unsettling, as are his photographs Local Shades – Nuancier [Colour Chart, because you get the impression that they have been touched up. His installations, two-sided modules, are constructed with the lighting which is also an important parameter which has to be managed by the exhibition photographer. These views, incidentally, are not credited; it is perhaps necessary for them to remain authorless documents, so as not to create any ambiguity with the work. We find this situation involving several levels of representation in the imagery of Fabienne Ballandra, who produces productions of photos of current events as re-photographed maquettes. The dossier gives priority to the live image, but a detailed caption is required to describe the result. We find this ambivalence again with Briac Leprêtre's water-colours which look like the views of his shows.

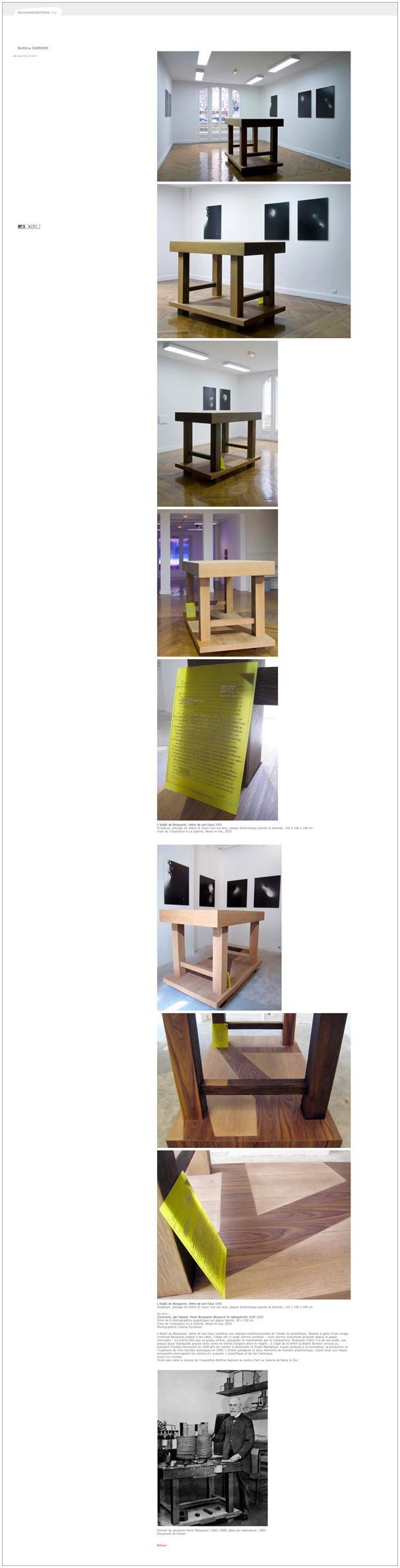

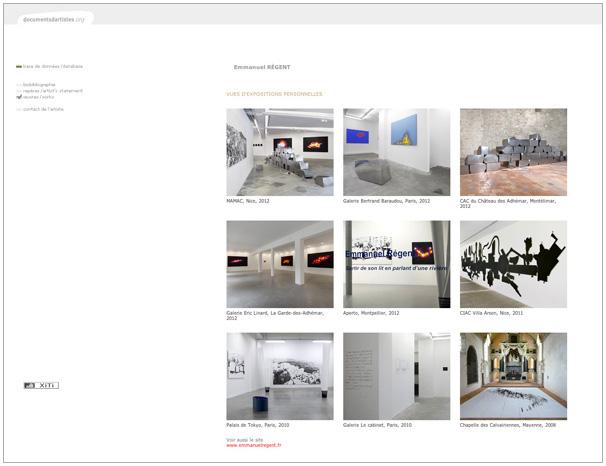

An ever increasing number of artists are becoming involved in the issues of display. For each project, Bettina Samson presents a series of views of the exhibition making it possible to understand the logic of the hanging, but if at times she produces large pieces, some are very small. General views help to document this ratio of scale. In a systematic way, close-up views follow on from the sequence to show details. The principle of presenting views of a work in different contexts is especially interesting. This photographic ensemble helps towards a greater objectivity not only by showing the work from different angles, but also in different lights. Demonstration is significant in Emmanuel Régent's dossier: if all the works exist for their own sake, their different associations, in different contexts, from the white cube to the baroque chapel, illustrate a line of thinking about the correlation between work and place.

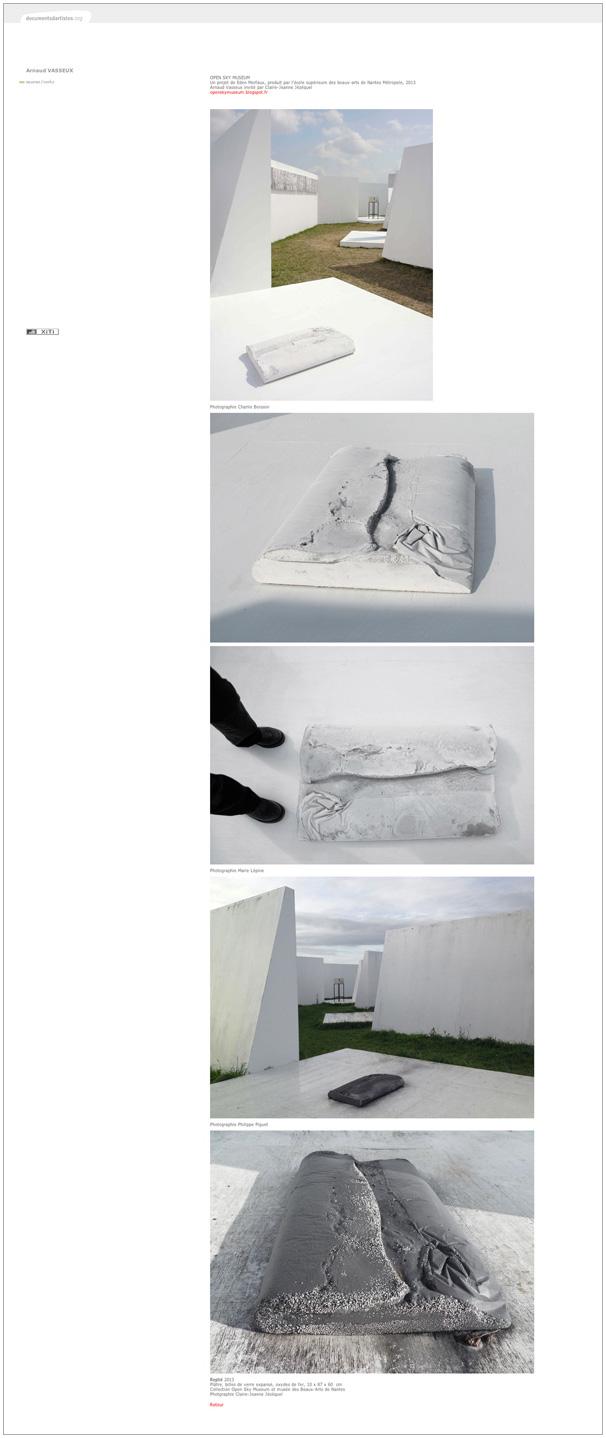

We once again find this work on the exhibition situation with Aïcha Hamu. The photographer of her show INNSMOUTH has constructed nothing less than a report which helps us to read the work of placement. It is the experience of the encounter with a work in an exhibition context which is documented. We can also understand the work Bucking Broadway, whose dimensions are adapted to the venue, in two contexts--a private foundation and a gallery—through the different way of looking at things adopted by another photographer. The exhibition views brought together in Arnaud Vasseux's dossier are especially aesthetic, with the works developing a certain photogenic quality through their breadth, their texture, and the work with light. But by entrusting the documentation to different ways of seeing things, especially for the piece Open Sky Museum, like the curator Claire-Jeanne Jézéquel and the critic Philippe Piguet, the artist does not impose a one-and-only viewpoint about his work. The exhibition view praxis makes it possible to dovetail different viewpoints without imposing a one-and-only perception.

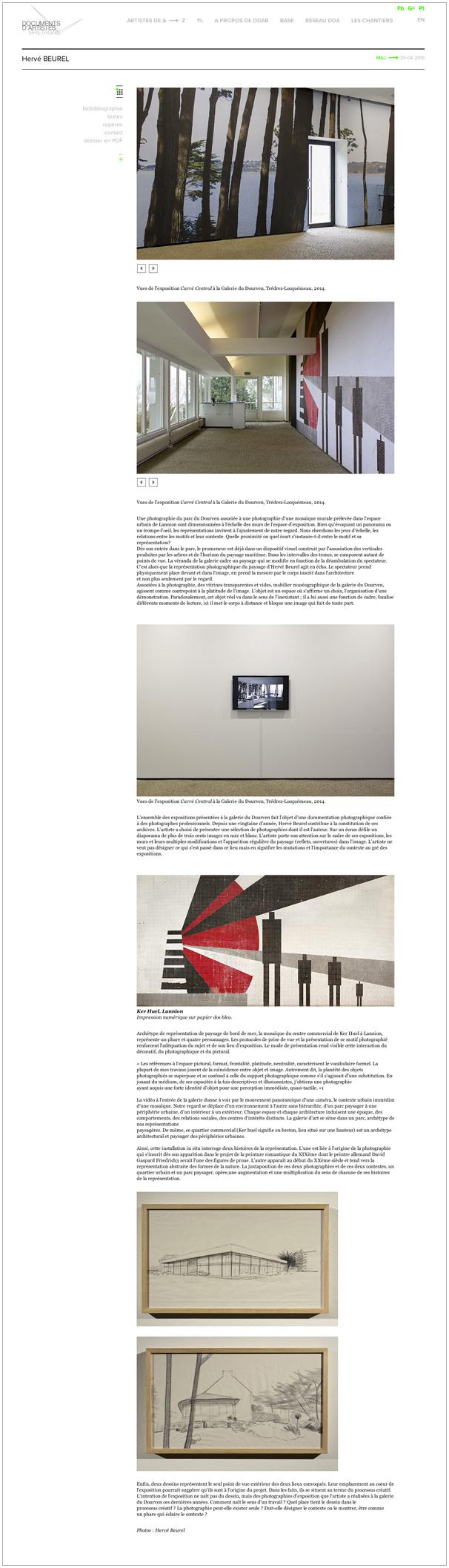

The selection of exhibitions on view at the Dourven gallery has been the subject of a photographic documentation. The artist Hervé Beurel took part in the production of these archives, and when he exhibits in this venue, he presents a slide show of 300 of his black and white photos. "The artist focuses his attention on the framework of these shows, the walls and their many different modifications, and the regular appearance of landscape (reflections, openings) in the image. He does not wish to designate what has taken place in this venue, but rather wants to signify their changes and the significance of the context from one show to the next".7 This slide show presented on a screen has itself been the subject of an exhibition view, in the dossier.

So the exhibition view photograph offers solutions for documenting a body of work and re-presenting it online. The image remains a document, while still being the interpretation of a work by an author (the photographer, the artist, the critic...) in one place in particular, at a given moment. The photograph does not replace the work, it is the vehicle, a way of looking. Unlike a photographic reproduction, a distance comes across like an interstice of thought, and calls for an awareness—these images are not transparent.

2-If the exhibition is an increasingly obvious way of discovering today's art praxes, it is not a criterion for browsing the DDA databases.

It is works that are represented; the approach by title or exhibition venue remains transversal. This is the major difference with the site of an artist, a gallery, or an institution, when it will present an "expography".

In regional databases, it is possible to make an advanced research, through keywords such as "anthropology", "feminism" and "utopia", but also "blah-blah" and "the big show". The list of words proposed is not the same on the two websites (it's the artist who comes up with words). An internal search engine makes it possible to make an "open search" and specify a search area in headings like "works", "residencies", "bibliography" and also "exhibitions".

Documenting works and exhibitions in the context of the Web encourages an awareness of the challenges of perception with regard to the work. This is attested to by the work of image selection. It is not a matter of using the most aesthetic, the most beautiful, the most suitable or the most effective, the one which will help to understand the work. The idea of re-thinking the work for the digital context is another solution, which involves a line of thinking based on the notion of document. At this level, consultation of the DDA databases brings out a generational difference in document use. Exhibition views are used more by young artists, who don't hesitate to re-contextualize this type of document.

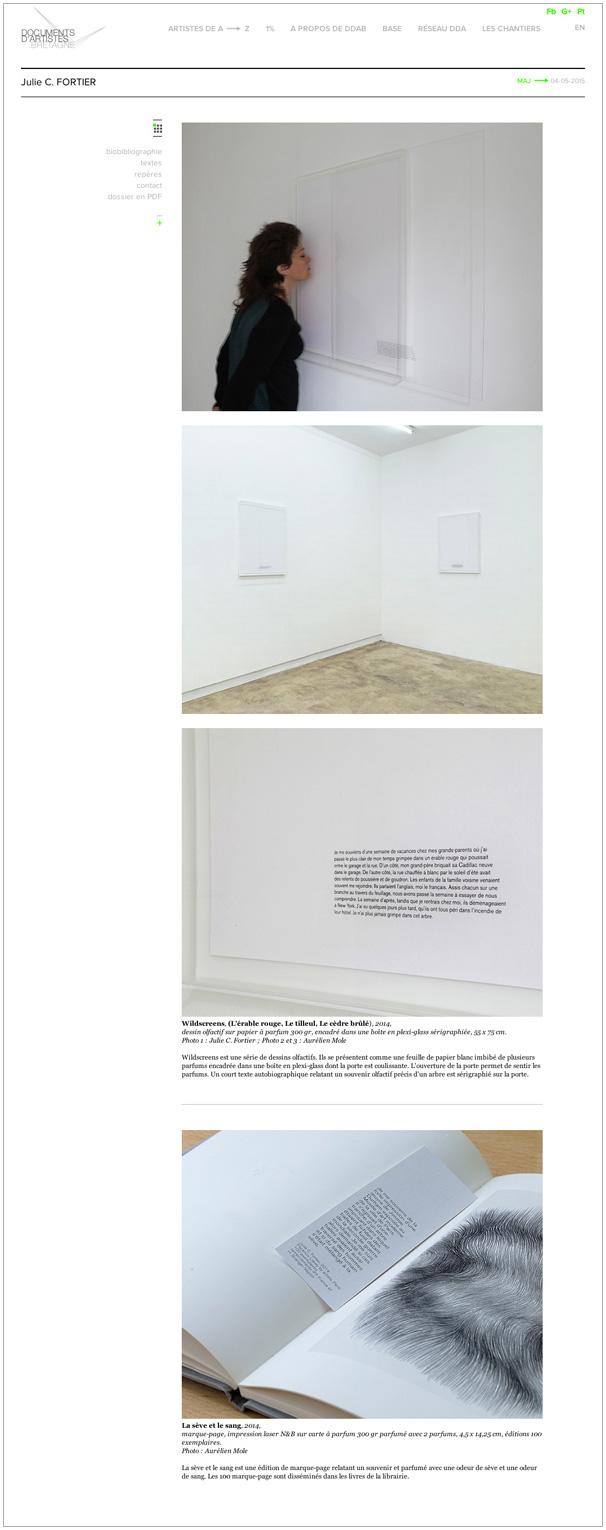

The exhibition view introduces solutions for documenting practices which are developed in situ, in relation with the place, or involving a way of thinking about the display, the process, the performative aspect, and the time frame. But this type of document may also be ill-suited to the work of artists working with and on sound, music, or smell. Even if it is sometimes possible to produce meaning by documenting the work in a visual way. Examples are few and far between in art history, but we can mention the particularly spot-on approach of Ugo Mulas in relation to the work of Sarkis8 and Kounellis9 in the '1970s.

The recent part of Julie C. Fortier's work is being developed around smells and food, which she presents in the form of exhibitions, but also performances. For La chasse, a site-specific olfactory installation, two photos are required, a general view taken by the artist and a detailed view by the photographer Aurélien Mole. Without the caption which explains that 80,000 perfume touches are involved, the work's essence is not perceptible. In the exhibition and performance views, there are often visitors or the artist herself striking poses, their gestures symptomatic of the action of smelling and breathing. The public's reactions in Damien Marchal's exhibition views help us to understand the presence of sound and its role in the piece.

Olivier Millagou works with a wide variety of media to create environments in which music plays a part as much in terms of imagery as of sound. Some of his projects in his dossier are accompanied by a sound track, like an attempt to describe the multi-sensorial character of his work. The distinctive feature of Marcel Dinahet's dossier is that it proposes a filmed documentation of his shows, which is added to a general view. In producing video installations, the fact that the artist uses the same medium for documenting them certainly makes sense.

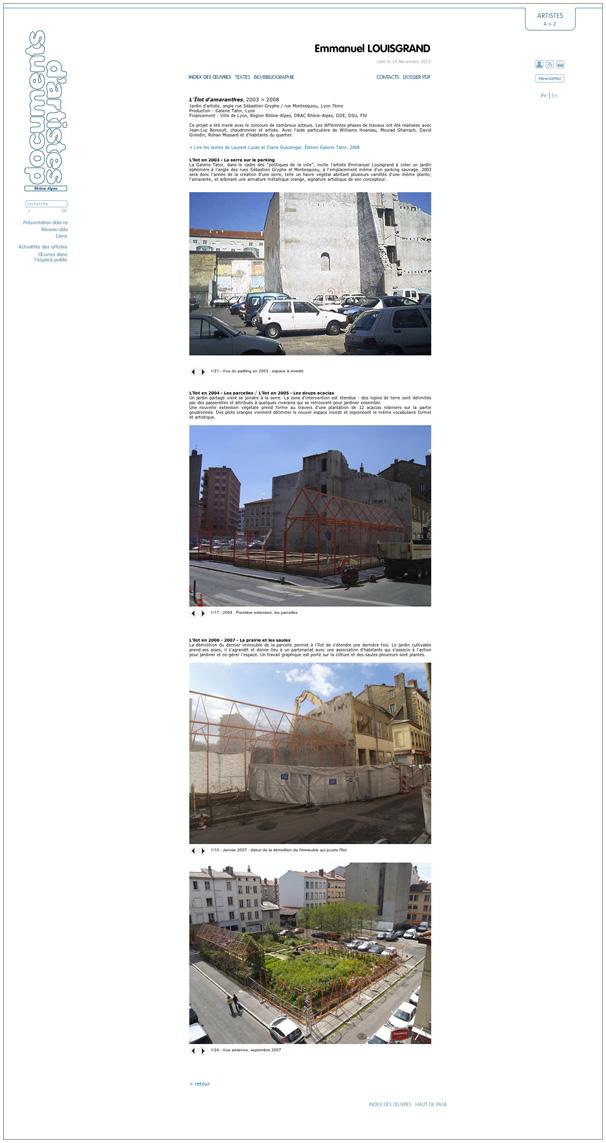

Emmanuel Louisgrand is an artist-cum-gardener. His work cannot be dissociated from the place, but in the end he rarely exhibits in galleries and art centres. This links up with the issues of land art, from the 1960s to the present day. But if many artists adopting this praxis transform their work into photos (which—for their part—will be exhibited and sold in galleries)10, the many photos taken by Louisgrand are just traces and clues, and not icons. This makes it possible to see the way the work is developing, and how a project can span several years.

3-Some artists are involved in visual documentation, confirming the nature of their relation with the exhibition. They are attentive to the statuses of the photographs, and steer the photographer by suggesting a viewpoint while at the same time explaining their approach.

In some instances, the photographer is no longer just a technical back-up, his experience of the work and/or place comes into the picture. This, nevertheless, is not systematically mentioned in the caption. The presence of this information, like the title of the exhibition where the work is being shown, the date, the place, and also the curator's name, specify the degree of significance given by the artist to the various exhibitions of his work, otherwise put, to the many meanings of his works created by the differing contexts.

These images in the artists' dossiers in the DDA databases have a precise function, which is either to document one work in particular in the manner of a classic reproduction, or to document the way in which it is exhibited, in relation to the place, and other works. We thus find two types of exhibition views: general views which document a hanging, or an installation, and views which frame one work in particular. In this latter case, the exhibition where the work is being shown is rarely mentioned. Yet what is involved is an occurrence of presentation at a given moment in a specific venue.

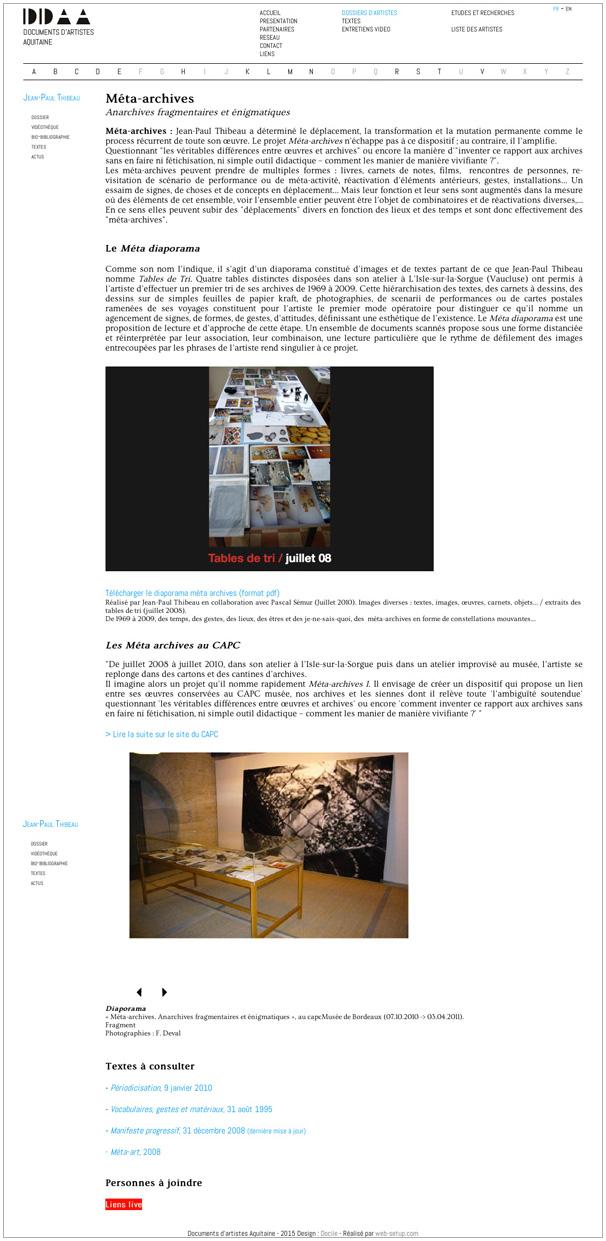

Some artists are developing a line of thinking about the issue of documentation and specific documentary methods, about the exhibition archive, and more generally about the documentation of their work. Their presence in the DDA databases and the form taken by the dossier are instructive. This is the case with Jean-Paul Thibeau and the project Méta-archives. Anarchives fragmentaires et énigmatiques, in which he questions the real differences between works and archives which may assume many different forms. In his dossier he presents the Méta-diaporama [slide show], formed by images and texts originating from his "sorting tables". These four tables arranged in his studio permit him to work on archives ranging from 1969 to 2009, by singling out a "reading arrangement". These tables have also permitted the creation of an arrangement shown at the CAPC, Museum of Contemporary Art, in Bordeaux, in liaison with the artist's works held in this museum. Another slide show made with photos taken by Frédéric Deval, the CAPC's photographer, document this show.

The dossier of Bernadette Genée and Alain Le Borgne is made up of a large number of different kinds of photographs. All their work revolves around the archive and the document. Each project is illustrated by exhibition views, photographs of openings, performances, and installations, as well as documents which have been used in the preparation process, like reproductions of photographic works. The diversity of the documents involves a complex directory structure with several indexes. The editorial production is presented with photos taken by the artists just as for the other images, and we can raise questions about their status.

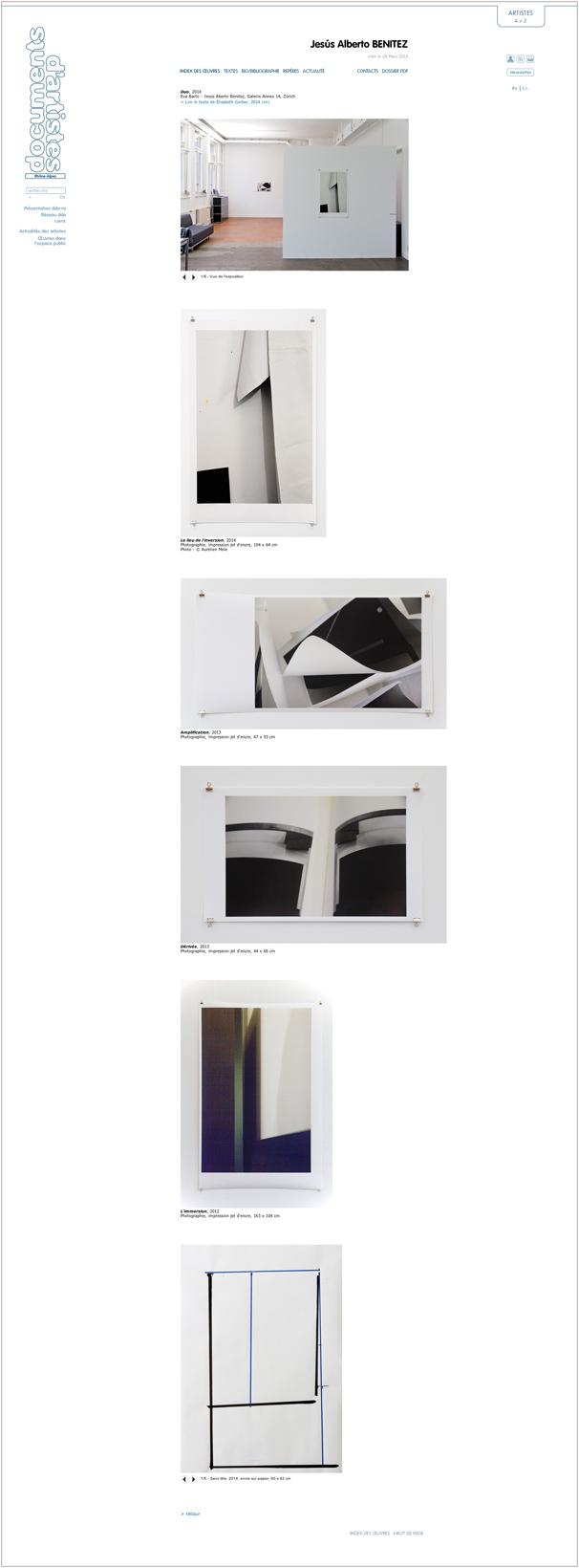

We find this ambiguity between the work and its documentation once again in the work of Jesus Alberto Benitez. For each project, a slide show systematically presents the exhibition views followed by reproductions of photographs and drawings. He explains: "With the wall, the images become installation objects. The interaction with the place extends the questioning of space which takes place in every image. The apparently empty space around a sheet of paper is always filled by real space. The ephemeral nature of a hanging is compared with the apparent permanence of photographic prints and drawings".11

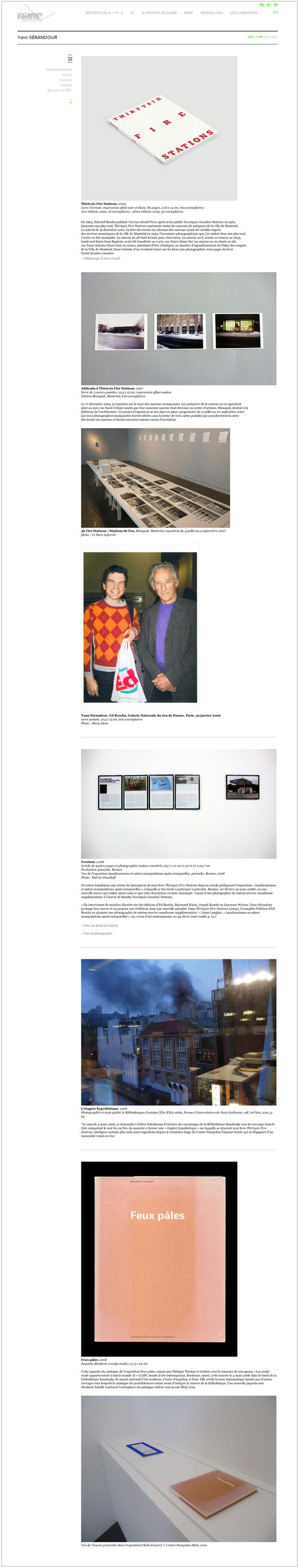

The relation between text and images is decisive in Yann Sérandour's dossier as well as in his approach, and in a way the development of the interface extends his publishing praxis. Work documents and exhibition views rub shoulders and fuel each other for every project. The dossier appears like an object per se. It must also be compared with the different graphic arrangement proposed by the PDF version which can be downloaded. Each medium involves a different transcription and reading based on one and the same object, bringing out, implicitly, the specific features of an art praxis broaching editorial reflection—in Sérandour's case, the text/image relation.

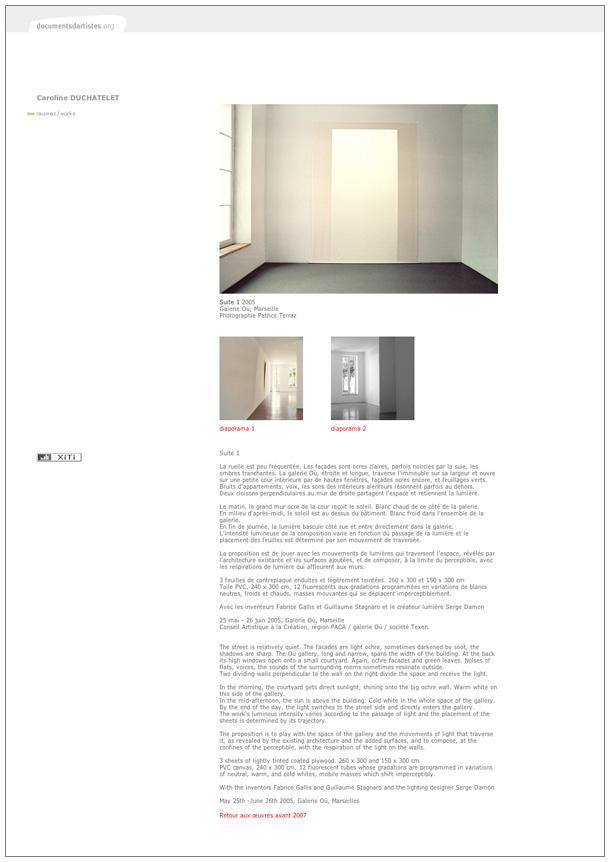

Caroline Duchatelet is involved in a specific form of documentation to present her work. Several photographs are required to record the effect of the variation of light on her works. The slide show sequence makes it possible to render the changes of light, and the interplay of highlights and colours, perceptible. In a way, the task of documentation using photography reveals the challenges of perception.

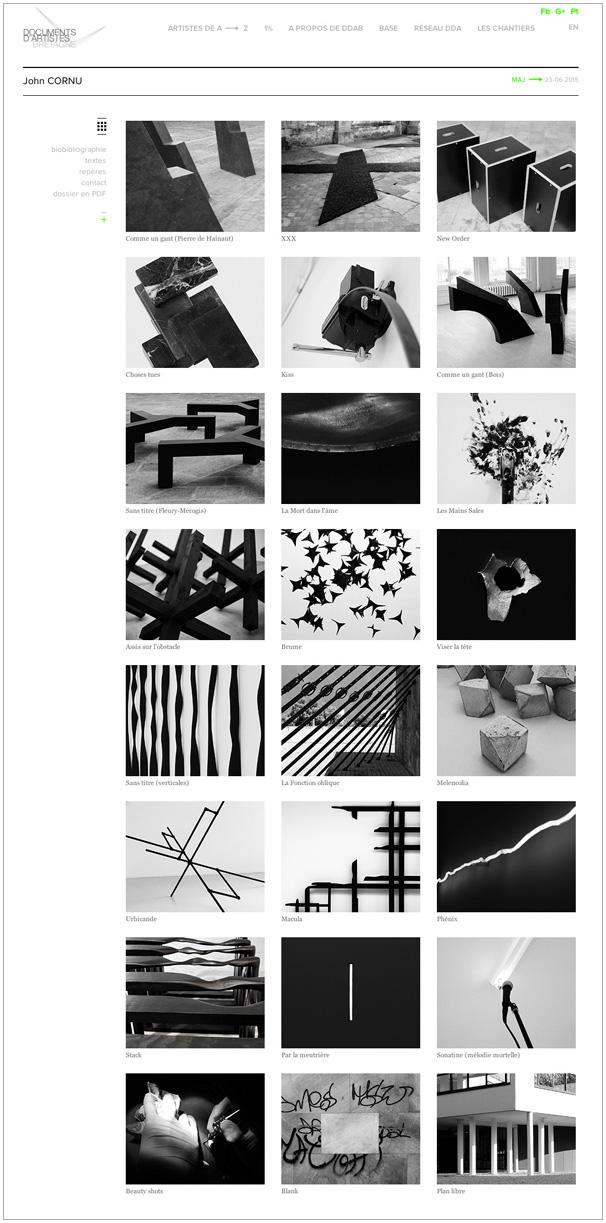

John Cornu produces most of the exhibition views in his dossier; he reworks all his black and white photos. As with Sérandour, the work has been rethought for the online dossier, it is not just a matter of regrouping different projects and shows in headings. Cornu's documents resemble his works while at the same time remaining tools for presenting the work, even if one may question the aesthetics brought about by this photographic ensemble. The black and white photograph is often associated with the objectivity of documentary praxis on the one hand, as the work of the Bechers attests to, but also with humanistic photography, on the other hand. Today, this paradox reveals our relation to the documentary image, which may be as functional as it is aesthetic. With digital technology, the colour photograph is increasingly precise, and using black and white becomes a choice, a voluntary approach and no longer a constraint. In a way, John Cornu extends his work with this documentary choice, and we find a coherence in the presentation, with the showing of the works making use of contrasts between black and white and its representation in shades of grey.

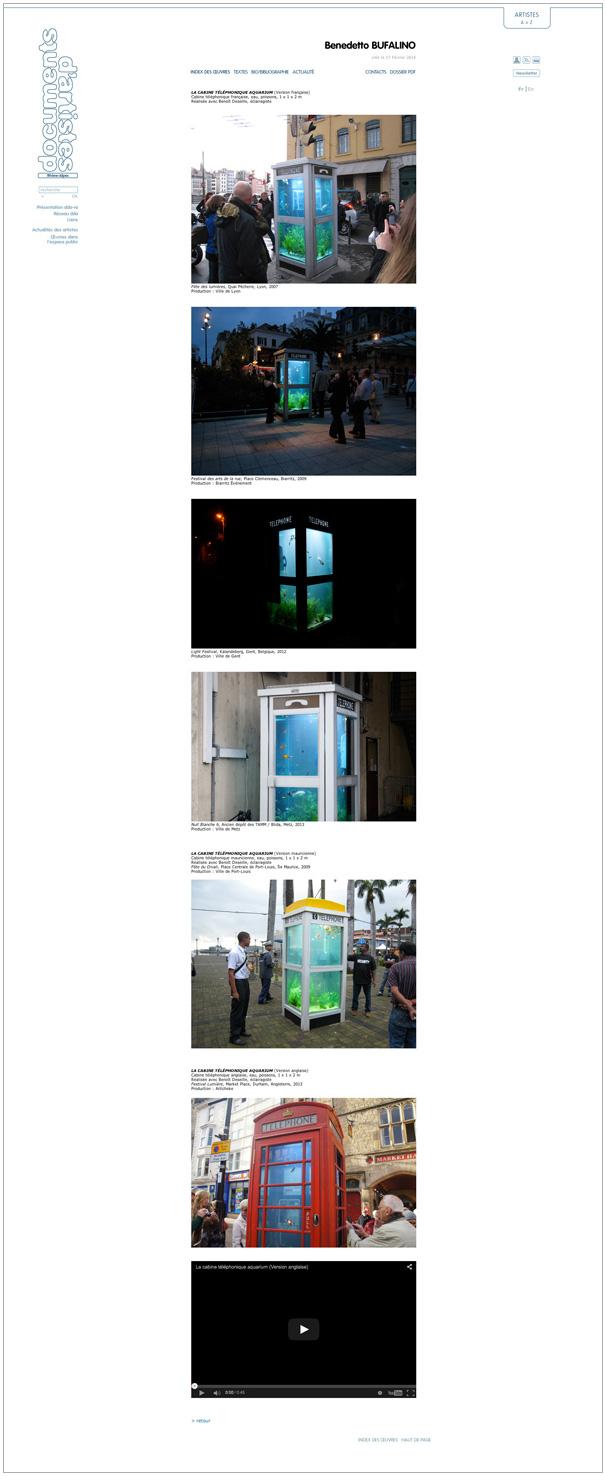

Benedetto Bufalino's work is mainly designed for the public place. Probably because of the fleeting nature of his projects, the artist has a special relation with their documentation. For each work, he produces or selects an emblematic image, which acts at once as visual memory and communication tool. His Internet site (more radical than his DDA dossier) presents a single image per project, while his actions involve spatial, temporal and relational deployments. Because of their situation in the public place and their marked propensity for "creating imagery", his works are regularly the subject of amateur photographs distributed on the Internet, thus giving rise to an "external" documentary circulation, which the artist pays heed to. In his dossier there are also slide shows revealing how the pieces are made. The function of these images is not to represent the works or reproduce them, but to provide information about the artistic method.

In the Documents d'Artistes databases, many dossiers are visually documented by the artists themselves, and their involvement in this documentation does not necessarily have to do with economic reasons (the question is thus raised about the control of distribution as well as the subjectivity of the way of looking at the work). However, we find in the dossiers professional photographers who are recognized in the domain, such as Marc Domage, Florian Kleinefenn, and André Morin; lastly, only a handful of them are attached to a geographical area, such as Blaise Adilon in the Rhône-Alpes region, and Jean Brasille and Jean-Christophe Lett in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region (PACA). They are developing documentary work with an approach that is trying to have an objective eye, and they are accustomed to working with places. Their images are probably wrongly regarded as neutral. Those commissioning their works are usually galleries, museums and art centres, and only rarely artists, but these latter sometimes have preferences for working with a particular person. The dialogue is sometimes fruitful and is constructed over time, with the photographer incarnating an "official" way of looking at the work, a viewpoint which is endorsed and monitored by the artist. The art historian Werner Spies says, for example, of the photographer Wolfgang Wolz that he is Christo's eye.

There is also the issue of the photogenic nature of the work; some works are more easily transcribed by photos than others. Certain very persuasive pieces lose a great deal in being documented by photographs, while others, on the contrary, gain in value. Especially with digital technology, it is possible to "arrange" a work by photographing it. Certain works, moreover, exist only to be photographed and are only distributed through this medium. Thanks to editing, it is also possible to show a work in a place where it has never been exhibited, and it is also possible to erase other works in order to show just a single piece. Simulating works in venues may be a praxis (artistic or curatorial), but this may also help to devise the hanging. The digital image is in any event retouched, which raises the question of the validity of these images and the existence of the work.12

*

For 15 years or so, Aby Warburg's work has enjoyed an evident revival of interest, in particular among artists, with certain theoreticians seeing an iconographical tendency in it. His project Mnemosyne, a large atlas of images, is most certainly an ancestor of today's image databases. It was designed to give visibility to the relations between different forms, cultures, and periods, by dint of the editing of an art history with no text, and the void which separated the images counted for just as much. Warburg evoked an "iconology of the interval" where the void is a space of thought.

Often regarded as the first art historian, by developing, through comparing works, a typology of styles based on pairs of categories, Heinrich Wölfflin was the first person to use two slide projectors in his classes.

The liaison of documents, the development of links, and analogy thus lie at the heart of art historical methodology.

This is also the principle of curatorial practice, comparing not only documents but also works in a place and an environment, with the aim of creating meaning, and even formalizing an argument. Nowadays, what is more, we find among many artists an approach consisting in using the documentary image, extracting it and changing the context, and reorganizing its display. Baptiste Croze's project Marc Domage, Rétrospective Art Press, 2007-2011 is an example of this. In the magazine Art Press he has cut out the photographs credited to Marc Domage between 2007 and 2011, and made an archive of them, which he presents in exhibition form. Jérôme Saint Loubert-Bié produced a similar project, but working directly with Marc Domage, so through its exhibition, in this particular case, the documentary approach became a fully-fledged work.

Today, the mechanical reproducibility of the art work as theorized by Benjamin leads to the digital reproducibility of the exhibition as formulated by Georges Didi-Huberman.13 The digitization of exhibition archives helps to write the history but it also has consequences for its conceptualization and its evolution.14 The very recent example of the invitation of 40mcube to the Bien Gallery and the artist Babeth Rambault underscores this by proposing a programme which is developed on the Internet: "The exhibitions proposed cannot be visited but they can be re-created by a single photograph, taken systematically from the same viewpoint".15

The 79 panels on which are arranged the 2000 reproductions which made up Warburg's Atlas Mnemosyne, originally on view in his library, are today the subject of displays, particularly with a scientific angle.16 It is thus possible, once again, to proceed like Warburg and Wölfflin, who had in a way anticipated digital technology with multiple windows opening simultaneously or successively, and hypertext links. As we have seen, however, there is still no application or programme permitting, in online databases, this exercise of comparisons and overlaps between documents. Transposing a database like Document d'Artistes in exhibition form would certainly, by way of an exercise of duplication and correlation, make it possible to think about the challenges of representing the works on view, online distribution, and dematerialization.

Remi Parcollet

Translated by Simon Pleasance,

in partnership with the CNAP | Centre national des arts plastiques

Notes :

1. "Une édition exposée", "Exposer la recherché", in the catalogue On ne se souvient que des photographies, at Bétonsalon (12 September – 23 November 2013), September 2013.

2. Giroud Véronique, "Support de recherche, la photographie est l'outil d'une possible archéologie du visuel, et un élément essentiel de l'appareil critique de l'histoire de l'art", "Le sens de l'histoire, la photographie destinée à l'archive", Art Press spécial, "Oublier l'exposition", (2000), n°21, p.110-115.

3. Anne-Lou Vicente, Raphaël Brunel, Antoine Marchand, "Entretien avec la revue Postdocument", in the catalogue Le tamis et le sable, Maison Populaire de Montreuil, 2013.

4. The first database was the PACA region's, which has been developed since 1999 and has about half the dossiers--some 200. Documents d'artistes Bretagne was set up in 2009, then Rhône-Alpes and Aquitaine in 2011 and 2012. The Réseau DDA, an association of regional projects, was founded in 2011.

5. By insisting on Gcoll software to manage their collections and Navigart to distribute them. On these issues see: Documenter les collections des musées. Investigation, inventaire, numérisation et diffusion, edited by Claire Merleau-Ponty, La documentation française, collection Musées Mondes, 2014.

6. Exchanges with the DDA teams on 2 July 2015.

7. Text taken from the online artist's dossier, which can be consulted by clicking here.

8. In 1970, Ugo Mulas photographed the first Sarkis show at the Musée d'Art Moderne. Seeing that the installation is made up of a tape recorder and that it was not plugged in, he questioned the artist. Sarkis explained to him the principle of the work and the sound accompanying it. Mulas then asked him to plug in the device so that he could photograph the exhibition.

9. Yannis Kounellis took part in the exhibition Vitalità del negativo nell'arte italiana in Rome in 1970. His work consisted in putting a piano in a large neutral space: twice a day, a pianist came and played a partly modified piece of Verdi's "Nabucco" for a few hours, and the music thus became an obsessive motif. Faced with this work, Ugo Mulas explains his approach: "My intention was to transmit the sense of obsession produced by the repetition of the music as well as the sense of musical time which is antithetical to photographic time. Photo after photo, while the image remained motionless, because I always stayed in my position and the pianist's movements were barely perceptible in such a large space; the music kept on coming and going, enclosing me in a sort of circle.

The result was a whole film of 36 almost identical shots (click here to see the work). There are 36 of them, not because of my choice, but because the film only allows 36. In the contact sheet the numbers are printed on the edge of the film and follow one another along the fixed image: without their presence, you might think that 36 repeated photos were involved. (...)

Time acquires an abstract dimension. In photography it does not function naturally, as happens for film and literature: different times are simultaneously present on the same sheet, (...). Calm is more effective than any kind of real movement, it is the obsessiveness of the repeated image that makes the dimension of photographic time".

Ugo Mulas, Il tempo fotografico, a text that is part of the "Verifiche".

10. Remi Parcollet, "Les photos souvenirs, l'autre outil visuel de Daniel Buren", Revue 20/27, n°6, March 2012.

11. Text taken from the online artist's dossier. Click here to consult.

12. Interview with Artie Vierkant, Zérodeux, summer 2014.

13. Remi Parcollet, "Figures du "photomural" exposé", Art Press 2, "Les expositions à l'ère de leur reproductibilité", February-March-April 2015.

14. Remi Parcollet, Léa-Catherine Szacka, "Ecrire l'histoire des expositions : réflexions sur la constitution d'un catalogue raisonné d'expositions", in Gérard Regimbeau (ed.), Culture et musée n°22, Documenter les collections, cataloguer l'exposition, Actes Sud, 2014.

15. The BIEN gallery is a gallery maquette where artists are invited to design an exhibition. The gallery goes to the artist, in his studio, and each art work is photographed by Babeth Rambault. "A game with rules that are both defined and flexible, the BIEN gallery broaches the issue of the exhibition – there being many artists producing maquettes and simulations of their future shows--as well as its survival. Because some exhibitions are little seen, they only exist through their photographic and written record. Others may also be more powerful in images than in real life... The BIEN gallery's project also reveals the role of the Internet which widely distributes images while at the same time de-contextualizing them. Last of all it highlights the way of documenting works and shows: tight framing, spaces with no human presence, turning our exhibition venues into interchangeable white and neutral spaces".

16. In 2004, in Venice, at the Palazzo Levi, there was the exhibition Mnemosyne Ite per Labyrinthum whose idea was to re-create the illustrations of the Mnemosyne-Atlas d'Aby Warburg. The Italian magazine Engramma henceforth offers on its website a detailed view of each panel, with all the iconographic references ("slides") associated therewith.

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Aquitaine

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Paca

Documents d’artistes Bretagne

Documents d’artistes Rhône-Alpes