Art dehors / Outdoor art

How are works to be installed outdoors? The outdoors is the landscape and the environment, as a place and its history, and the people who bring life to it, with their imagination and their projects. Not a whole lot to do with “the public place”. To put things in a nutshell, let us say that “the public place” is to the city what the white cube is to art worlds. By de-contextualizing, and being universalist and quality-less, it turns out to be an arrangement of ostentation and even of domination. An indoors without an outdoors. As for works installed “in the public place”, they are the instruments of variables which describe them as such, in the sense in which Walter Benjamin talks about the “aestheticization of politics”. Often set in the centre, isolated as a result of their more or less imposing pedestal, and forcing visitors to walk round and round them, they express all the better the order which is their commissioning body, because they are detached from space-time circumstances peculiar to the spaces of their installation. Whether they are outdoors or indoors is thus of no importance. Ideally, outdoor works are not “in the public place”, but connected to public places and interacting with them. They inhabit these places, and sometimes reveal them; in other instances, they create them. At times, the works themselves are places, like the sculptures of Carl Andre which he defined as “sculpture as place”—the thing with which he identified his specific contribution to art history. Outdoor art is thus not in situ.

The outdoor exercise is used by a large number of artists present in the collections of the Réseau documents d’artistes, often by way of specific structures: Voyons voir in the Sainte-Victoire region, Domaine du Château d’Avignon in the Camargue, La Forêt d’art contemporain in the Landes, Le Vent des forêts in the Meuse, Cairn centre d’art in the Alps, Rives de Saône in Lyon, Estuaire in Nantes, etc. This is a hazardous exercise. The outdoor way of life, here synonymous with the capacity to create a place, is far less rooted in our habits and reflexes than indoor lifestyles, within four walls, with the door shut, protected from bad weather. If the proposals of artists and their patrons run the risk of being put in a dominant position in the face of an environment which they ignore or about which they make mistakes, they are also faced with the danger of seeming trivial or simply superfluous in relation to what is already there. By leaving aside proposals which, in my view, are failures, and by regretting that exhaustiveness is impossible here, I suggest that we visit some of them and make the most of our visits to highlight the different methods of shared experience of a place which they bear witness to.

Roland Cognet's Poutre et chêne [Beam and Oak]1, provides a good introduction. What this work expresses with regard to relations between the human being and nature is richer and more relevant than many theories. Unlike a statued sculpture (like, for example, the Chaufferie avec cheminée, installed in front of the MAC Val in the middle of a huge roundabout, in total contradiction with the work of Dubuffet who is its creator), this work is closely linked to the oak tree which it supports and brings back into balance. Incorporated within its general structure, it increases its longevity.

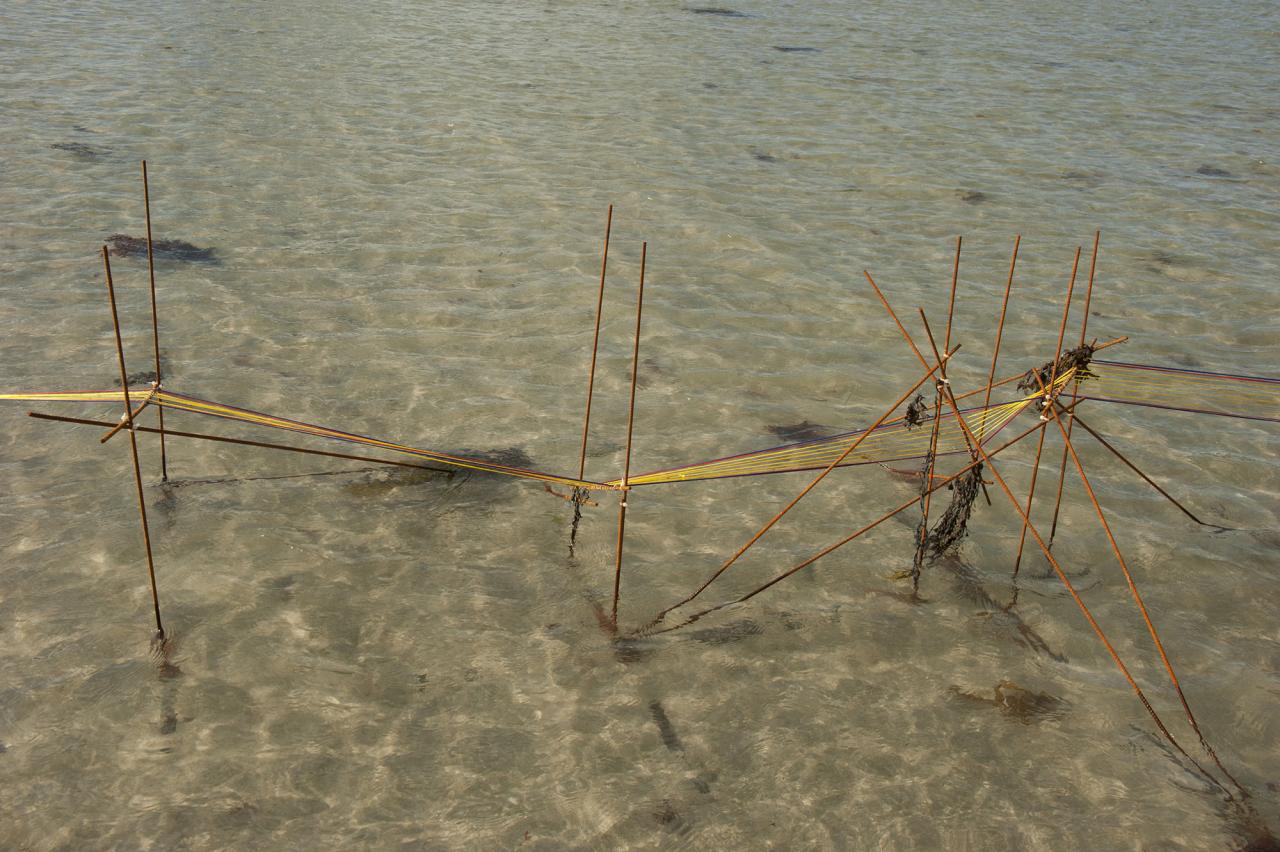

Nevertheless, being incorporated is neither being assimilated nor merging. The oak and the beam are not merged, and the title indicates this clearly. If the work is part and parcel of nature, it is however not a part of it. It is, on the contrary, totally individualized, surprising, independent of the logic of the tree accompanying it, at the right distance, and assumed as an artefact. The fact is that the combination between integration and disjunction is a good image not only of outdoor art, but also, let it be said in passing, of typically democratic lifestyles. Another example is to be found with Nicolas Momein’s installation éphémère 2, and Ron Haselden's Sealife 3, which, while re-using materials and motifs peculiar to ocean tides and fishing, acts from the beach like a trap, in its turn trapped.

This type of interaction is not exclusive to sculpture. Captations et installations sonores (Patrice Carré), land, walk and mapping surveys (Hendrick Sturm), video installation performances (Olivier Crouzel, La Cuze, 2015), and light panels and photographs (Vincent Bonnet, Hypersujets) may all stem from this in differing degrees. The important thing is to find that balance exemplified by the beam and its oak, which is to say that somehow “ecological” situation in which the elements present are not dissolved by one another but, on the contrary, work together to maintain it, and incorporate it within a larger context which forms its horizon of meanings and possibilities of being. For example, while Bruno Peinado, avec Sans titre, Close Encounters, favours Marseille as a meeting place of the 3rd kind, Sylvie Ungauer’s, Data Horizon 4 transforms the waiting and transit area represented by a tram station into a place of possible experience. For a split second, the traveller becomes an onlooker. In deciphering the on-screen data and by interacting with the screen, the utilizer becomes a user.

Specific phenomena happen outdoors which might not take place indoors. Well protected within an air-conditioned area, the most fragile of works survive. Exposed to bad weather, they have to be tough, and compact, and capable of adapting. The fact that the proposal is ephemeral does not change anything. We have seen pieces fly away, dissolve, become torn, and collapse with the effect of wind, sun, and rain, well before their time, no matter how close it might have been. As Thoreau said about thought and temperament, outdoor things are tailored to deal with (and not confront) nature, which is why they are “tanned by the sun”.

Many outdoor works do not talk solely with nature, but also with the social and historical environment, which is a decisive variable. Stéphane Bérard’s Mille plateaux-repas 5 is in-between. The larch wood with which the three tables are made and their slope are just as connected with nature as the picnic absurdly laid on the table; the alignment and the impression of artificial superposition are linked with our tourist ways. As far as the intersection between these two environments in which we see artificial superposition is concerned, it is revealed by the participation of visitors.

The place produced by the establishment of a relation with the surrounding space, as in the previous example, takes on a new quality: that of being produced by how it is used. Place and uses mutually involve one another: the uses are only what they are if the gestures which bring them into being are free, and the places are only what they are if they form a reserve of possible resources for eventual uses. This means that unlike, on the one hand, the utilization and, on the other hand, “total institutions” (Goffman), uses and places are plunged into a relation of mutual transformation. Compared to the uses invited by Bruce Nauman’s Stairways (1998-99), where the height of the steps is relative to the degree of the slope’s gradient, those permitted by Mille plateaux-repas are, in my opinion, a bit too restricted to fuel this experience of freedom via the development of the individuality which is the end-purpose of art. For all this, the wit, the quirkiness, and the playful quality which it contains mean that its activation is neither remote-controlled nor instrumental. The piece forms an altogether special place in the itinerary which they are stage of. Ibai Hernandorena’s Flying Carpet 6 also possesses the property of ensuring, by way of the emergence of a place, the connection between ground, forest, walkers and users.

The further we go towards the social and social relations, the more important it is to consider the resistance of works not only to bad weather, but also to users. The best way of creating a place in the city is to come up with installations which, because they are liked and become part of people’s everyday lives, become objects of attention and care. As has been shown by specialists in the upkeep of outdoor art, this is the best guarantee of resistance that there is 7. With Olivier Bedu’s Geckos #1 and #2 8, all the conditions are brought together. Somewhere between public sculpture and social facilitator, urbanity and civilities, conversation and game, furniture and stage, localness and cosmopolitanism, the Geckos have been jointly designed and jointly produced. Because, without discounting the distinctive nature of Olivier Bedu’s work, the inhabitants were, from the outset, consulted and included in the arrangement, and because they are able to recognize in it a respectful mark of their contribution, they have naturally developed the habit of taking care of it.

By definition, a place includes a plurality, but, also by definition, it is based, too, on the harmony between the elements which make it. We can call the group that they form “community” and use the term “self-government” for their method of regulating the concrete spaces necessary for their existence. As Elinor Ostrom, Nobel Laureate in economics, has demonstrated with regard to “commons”, common goods presuppose a common government which preserves their communalization, which is to say their sharing.

With place-sculptures, a category of specific spaces is opened up. They neither reveal nor alter existing spaces, but bring on new places 9. Nicolas Floc’h’s La Patate chaude is a good example. It reminds me of a commission which winegrowers in the Champagne region placed in 2017 with the School of Architecture in Châlons-en-Champagne, involving the re-creation of vineyard huts which have vanished, thus condemning the winegrowers to the isolation and drab uniformity of endless vineyards and excessive productivism. La Patate chaude jostles the boundaries between traditionally defined spaces: agriculture, habitat, art, leisure, work, school, etc. Half-way between the incongruousness of Erwin Wurm’s potatoes and the realism of Penone’s pile of potatoes, it stems from the concern with “production of space” dear to Henri Lefebvre, which is such as to correlate the specific experience of a place, the plurality of the users, and the intensification of social relations. As a place of accommodation, study, discussion and repose, because of its at once familiar and non-geometric form, which is the special feature of potatoes in general, the work brings together, in a coherent whole, the organs of human sociability. Emmanuel Louisgrand’s Jardin Jet d’eau is another example of a place-sculpture: at once composite, integrated within the surrounding space, and connected with its ecological, economic, and political variables, it nevertheless forms a disjunctive and critical space in relation to the logic of urban deterioration in the Dakar neighbourhood in which it is installed.10.

These examples illustrate the, in my opinion, politically and ethically fundamental distinction between being “in the public place” and forming a public place. Shifting from one to the other is shifting from power to the power of action, from isolation to sociability, and, in a nutshell, from spectacle to participation. The fact that there are many opportunities for this in the sphere of contemporary art is a sign that art still has the power to reveal and explore possibilities of living together, which our activities, our representations, and our usual beliefs are burying and trying to get rid of.

Footnotes :

1 Roland Cognet, Poutre et chêne / Aux bords des paysages / Cazevieille (34), 2016

A sculpture produced as part of the circuit of in situ works, Aux bords des paysages, Communauté de communes du Grand Pic Saint-Loup and association Le Passe Muraille.

2 Nicolas Momein, 23 Habitants au km², 2012

An ephemeral installation , Egliseneuve d'Entraigues, pastures used by Salers cows (close to Falaitouse) made as part of Horizons “Arts-Nature” en Sancy #6. Some thirty totems made of salt stones are “sculpted” by fifty Salers cows and a bull.

3 Ron Haselden, Sealife, 2016, steel rods, fishing line, 25m long.

Plage de Toul Gwen, Ile grande, Côtes d'armor, Bretagne, France

Festival de l'Estran, Côte de Granit Rose, Bretagne, France

4 Sylvie Ungauer, Data Horizon, 2012

LED screen, totel of galvanized steel, adhesive with grey camouflage motif, camera, computer system

Dimensions : 3,40 m x 1,30 m x 25 cm

Commission by Brest Métropole Océane for the tram line, porte de Plouzané station.

5 2011, Le Vernet, lieu-dit de Lou Passavous, Route de l’art contemporain VIAPAC

6 Ibaï Hernandorena, Flying Carpet, 2007, Collection Vent des Forêts

7 See Derek Pullen and Jackie Heuman, « Modern and Contemporary Outdoor Sculpture Conservation, Challenges and Advances », p. 4, in The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, Volume 22, n°2, 2007, <getty.edu/conservation/publications>

8 Geckos #1 et #2, 2015, Ville de Marseille, Région PACA, Fondation de France and Fondation Logirem, Cité Bellevue, Marseille, 2015

9 La Patate Chaude, 2012, Jardins du Breil, Pacé, Ille-et-Vilaine

A work produced as part of the New Patrons Programme

10 Emmanuel Louisgrand, Jardin Jet d'eau, sculpture vivante, Dakar, 2014 - 2017

Inauguration in May 2014, for the Afropixel 4 Festival, during the Dakar Biennale. A work produced by the Senegalese association/legal NGO Kër Thiossane.

Photo : © Bernard Pauty - OT Sancy

Photo : © Bernard Pauty - OT Sancy

Photo : © Bernard Pauty - OT Sancy

Photo : Karine le Bris, Marcel Dinahet, Ron Haselden, Elin Karisson & Camille Lucas

Photo : Karine le Bris, Marcel Dinahet, Ron Haselden, Elin Karisson & Camille Lucas

Photo : Karine le Bris, Marcel Dinahet, Ron Haselden, Elin Karisson & Camille Lucas

Photo Frédéric Gillet

Photo Frédéric Gillet

Photo Frédéric Gillet

Wood, 5 x 3 x 0,5 m,

Vent des Forêts collection / Curator: Alexandre Bohn

Wood, 5 x 3 x 0,5 m,

Vent des Forêts collection / Curator: Alexandre Bohn

Photo Philippe Piron

Photo Philippe Piron

PhotoPhilippe Piron

Photo Philippe Piron