Stefan Eichhorn

News of the Future ?

Stefan Eichhorn lives and works in Marseille, where he set up home after a residency in the city’s northern suburbs, in 2014. The artist is especially fond of imagery to do with anticipation theories, among which we may come across new worlds resulting, according to Philip K. Dick, from “conceptual dislocation”.1 To do this, you have to proceed by way of the experience of the science-fiction hypothesis, and accept a cognitive distancing with regard to narrative and the certain confusion caused by a similarity with reality.

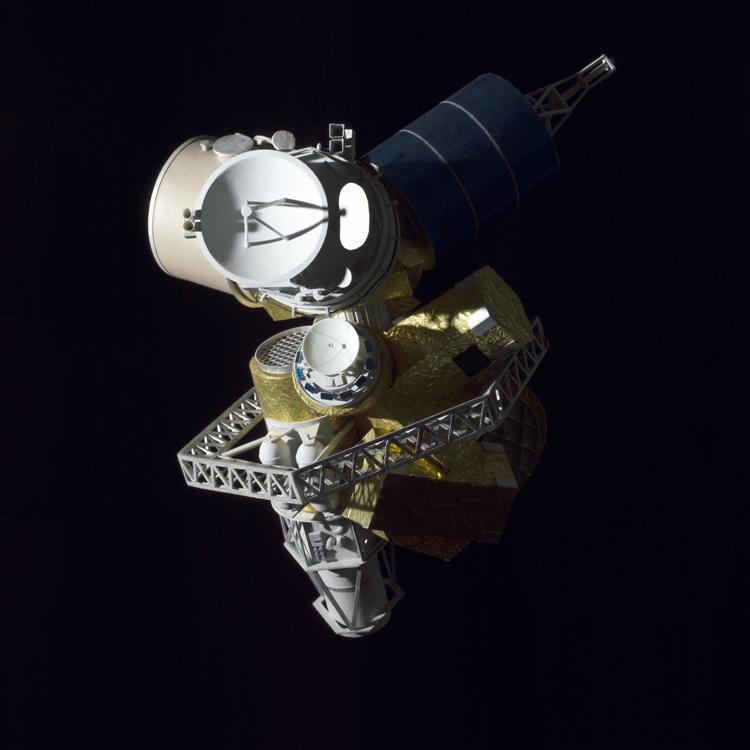

During a residency at the Observatory of the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), the artist produced the series Salvage 1 (2018), presenting a set of reconstructed satellites in the form of maquettes, then photographed like a complete pastiche of an orbital track against a black ground—thus bringing the illusion full circle. Only the descriptive literature about this will put you on the right track. A quick visit to the Internet site stuffin.space, mapping in real time the future satellite ghosts and other protagonists involved in a conquest of space will assume the task of persuading you.2 Stefan Eichhorn pays special attention to the detail of scientific language, from its populariziation to its most rational state, and his titles already tell us a lot about the author’s gentle irony: Ils nous ont promis des voitures volantes, mais nous n’avons que des parcmètres fonctionnant à l’énergie solaire (2019) [They promised us flying cars, but all we have is solar-powered parking-meters].

Among the many fictions applying the above-mentioned American author’s famous “conceptual dislocation”, a short story by Edward Morgan Forster, recently discovered thanks to a tip from the artist, also stands out. As a social and environmental dystopia dating from the early 20th century, La Machine s’arrête/The Machine Stops echoes strangely in the epidemiological crisis of the current health and economic crisis.3 Let us admit that the great bulk of humankind lives underground in individual cells, that all vital requirements are met by a machine, that communications only exist through a video-conference system permanently available, and delivering unlimited information about everything the human being wants to know: a lecture on the Mediterranean Sea, the history of acousmatic music, the practice of tantric yoga… Or to put in another way, let us suppose that elsewhere no longer exists, that tomorrow looks like today, and that science is capable of prolonging day and night by following the rhythm of the sun, and even surpassing it.

Over and above an anxiety-inducing similarity with reality, this short story introduces, above all, the themes of another form of science-fiction more broadly developed from the 1960s on. Less narrative and more political, this new science-fiction influenced by the American counter-culture prolongs its critical viewpoint in the face of society by proposing a line of thinking about ecology, sexuality, feminism, the role of the media, and the new technologies. In this respect, it marks Stefan Eichhorn’s interest during a residency in the United States. He focused, at that time, on Drop City—the first hippie community set up in a rural environment, in opposition to the US army’s engagement in the Vietnam war, and to multi-consumerist capitalist society. In 1965, that mixed bunch of people would borrow the model of the geodesic dome invented by Richard Buckminster Fuller,4 author of the famous Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, pinpointing the planet’s limited resources and the notion of ephemeralization defined as the “making more with less” tendency of technological progress. He was one of the first people to disseminate a systemic vision of our environment, but he is nevertheless better known as the inventor of the geodesic dome—a model bequeathed by Walther Bauersfeld5, of which he produced a more sophisticated and lasting model, with a dozen students at Black Mountain College during the summer of 1948. The American would subsequently sell that patent to the army and give lectures on that same subject until the end of his life. It was not until the early 1970s that media coverage of him would be carried on through a new environmental activism.

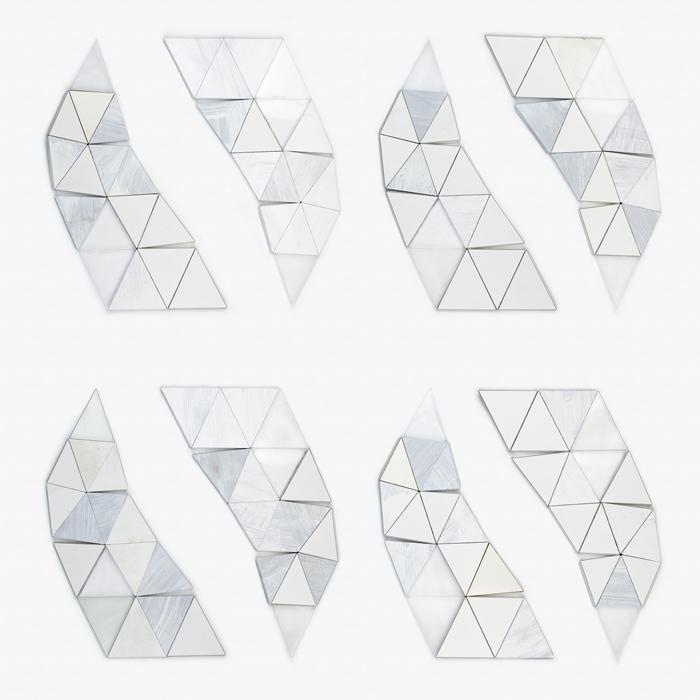

Stefan Eichhorn’s project, embarked upon when he returned to the United States, and titled Tents (2010-2019), thus proposed shifting the markers of the American counter-culture into the art arena. His fascination with that structure extended through several series of works, in particular Paper Models (2019), an exercise involving the reproduction on paper of the precepts of the geodesic dome popularized by Lloyd Kahn’s Domebook, Kahn being a pioneer of the movements for alternative architecture, and also the publisher of the famous Whole Earth Catalog.

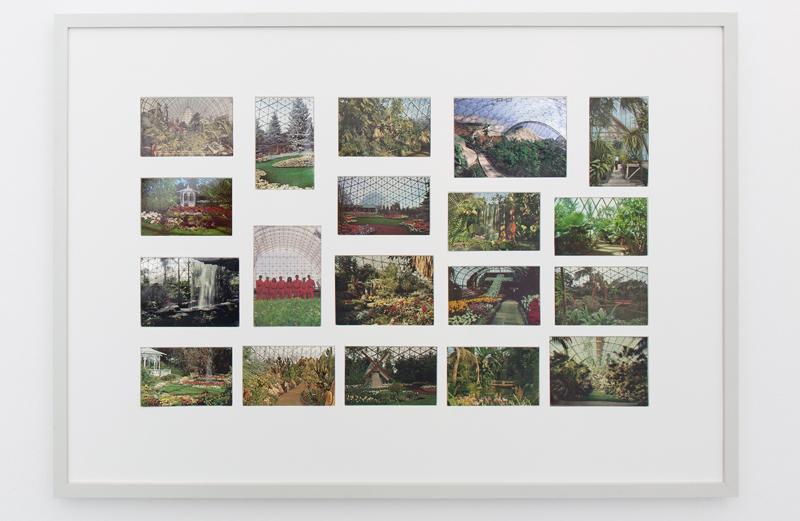

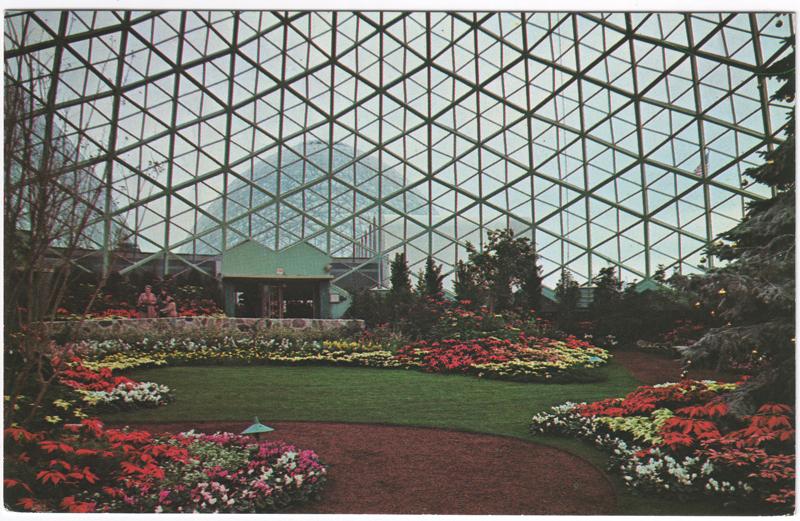

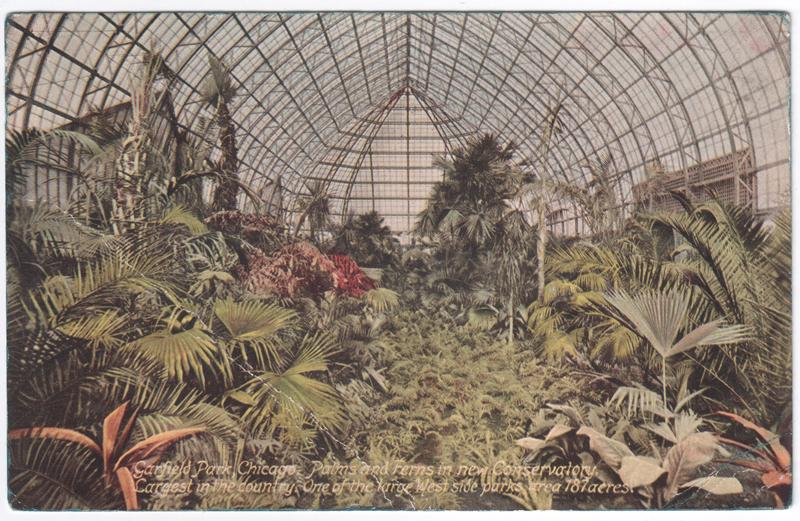

For the past ten years or so, Stefan Eichhorn has also been collecting representations of the geodesic dome, playing host to the most confined environments, from the most futurological to the least scientific. In the end of the day, the dome would thus be the image of a plural future—that of Bauersfeld’s planetarium, of Buckminster Fuller and of hippie communities reawakening our ecological consciousness, but also of private utopia. By the same token, the series Greetings from the Future (2013) sarcastically showed biospheres confined beneath greenhouses that were vestiges of the European industrial revolution, and flirted with survivalism.6 From all this resulted a broad panorama ranging from the Victorian age to the 1990s, the climax of which is probably still Biosphere II, an experimental site based in Arizona bringing several ecosystems together: a tropical forest, a desert, savannah, a marsh, an ocean and its coral reef, where occurred: “The most exciting project since the launch by John. F. Kennedy of the new space frontier”.7 The undertaking, which is still controversial in terms of its scientific viability, today features among the most visited sites in Arizona—just behind the Grand Canyon National Park.

Arlène Berceliot Courtin, May 2020.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Notes :

1. “This is our world dislocated by a certain kind of mental effort by the author, this is our world transformed into what it is not, or not yet. This world must be distinct at least in one way from the one that is given to us, and this way must be sufficient to permit events which cannot be produced in our society—or in any known society, present or past. There must be a coherent idea involved in this dislocation; which is to say that the dislocation must be conceptual, and not simply trivial or strange—herein lies the essence of science-fiction, a conceptual dislocation in society, in such a way that a new society is produced in the author’s mind, born on paper, and from that paper it produces a convulsive shock in the reader’s mind, the shock produced by a confused recognition. He knows that he is not reading a text about the real world”. Philip K. Dick, letter of 14 May 1981, Nouvelles 1947-1953, Editions Denoël, 2000.

2. Initiated in 2015 by the American engineer James Yoder, http://stuffin.space/ displays an interactive, real time card of the objects and satellites orbiting around the Earth. Daily updated, the data come from a base attached to the US Department of Defence. With different filters and possibilities of identifications, the site proposes following some 150,000 objects—excepting those involving national security. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (aka NASA), space debris poses a real risk for space craft and the way space missions are conducted. At the present time there are supposedly some 21,000 items of debris larger than 10 cm/4 inches.

3. The Machine Stops, Edward Morgan Forster, Editions Le Pas de Côte, 2014. The British author apparently wrote this short story by developing an acerbic technological future in response to the socialist optimism of Herbert George Wells, author of the Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man, and The War of the Worlds.

4. A geodesic dome is a hemispherical structure whose component triangular elements are rigid and distribute the stress throughout the structure.

5. Let us note that the first geodesic dome built was commissioned in 1922 by the German company Zeiss Optical Company from the engineer Walther Bauersfeld, in order to test their new planetarium projector on the roof of the company’s headquarters based in Iena.

6. Survivalism describes the activities of certain individuals or groups of individuals preparing for a catastrophe (be it economic or health-related) on a local or worldwide scale, or even for a potentially cataclysmic event (ecological collapse, nuclear war, extra-terrestrial invasion) or more generally for a collapse of industrial society. The movement came to the fore in the United States in the 1960s, within the political context of the Cold War.

7. Mal de l'air dans la biosphère, Christophe Alix, Libération, 14 août 2009. / Airsick in the Biosphere, Christophe Alix, Libération, August 14th 2009.

Série de 3 photographies, 70 x 70 cm chaque

Série de 3 photographies, 70 x 70 cm chaque

Foam, cloth zip, and other recuperation materials

Approximately 60 x 60 x 200 cm

Foam, cloth zip, and other recuperation materials

Approximately 60 x 60 x 200 cm (detail)

Cloth, zip, wood sticks, epoxy resin, fiber glass

Cloth, zip, wood sticks, epoxy resin, fiber glass

Cloth, zip, wood sticks, epoxy resin, fiber glass

Cloth, zip, wood sticks, epoxy resin, fiber glass

Cardboard, plastic, paint, Framed, 70 x 70 cm

Paper, cardboard, linoleum, aluminium. framed, 70 x 70 cm

Cardboard, paper. framed 70 x 70 cm

Postcard collection since 2013

Postcard collection since 2013

Postcard collection since 2013